Executive summary – what changed and why it matters

Maritime Fusion announced plans to build Yinsen, an eight‑meter tokamak designed to produce ~30 megawatts of electricity on a ship, targeting operation in 2032 and estimating a first‑unit cost of about $1.1 billion. The company has raised $4.5 million in seed funding, is assembling high‑temperature superconducting (HTS) cables from imported tape, and intends to perform some fuel processing on shore to simplify the marine install.

For operators and buyers, the substantive change is a repositioning of fusion from a grid‑scale, land‑based ambition to a niche early market: marine power where fuel costs are high and regulatory tradeoffs may make first‑of‑a‑kind fusion commercially defensible sooner than on the grid.

Key takeaways

- Scale and budget: Yinsen targets 30 MW, 8 m tokamak; Maritime pegs first‑unit capital at ~$1.1B (≈$36k per kW) and a 2032 operational goal.

- Capital mismatch: $4.5M seed is standard for early development, but orders‑of‑magnitude more funding will be required to build a billion‑dollar prototype.

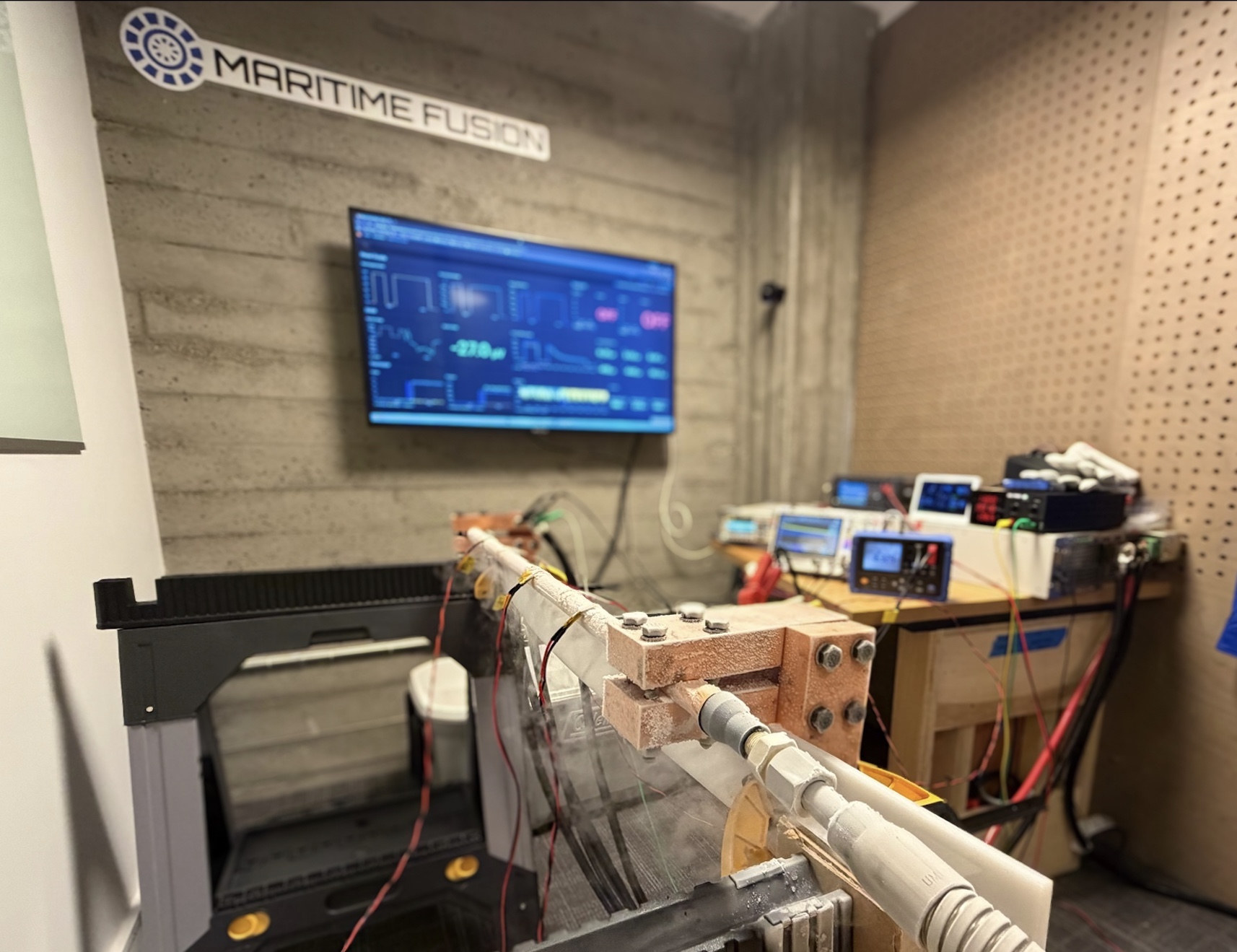

- Technology choice: HTS magnets (tape‑based) reduce magnet mass and size; Maritime is already assembling HTS cables and plans to sell them as an interim revenue stream.

- Market logic: Marine fuel (ammonia, hydrogen, low‑carbon fuels) is costly; early fusion could compete as a premium alternative for specialized ships or shore power, not the mass merchant fleet.

- Regulatory and operational risk: maritime certification, port permissions, insurance, neutron activation of ship materials, and emergency response protocols are open questions.

Breaking down the announcement

Maritime Fusion’s pitch rests on three technical and commercial premises: (1) available HTS magnet technology lets a tokamak be compact enough for a ship, (2) offloading fuel processing and some ancillaries to shore reduces onboard complexity, and (3) the marine fuel market can bear higher first‑of‑a‑kind costs than grid electricity markets. The company has started by assembling HTS cables from tape sourced mainly from Japanese suppliers and intends to sell those cables while it develops the plant.

Yinsen’s 30 MW nameplate is modest relative to large grid plants but meaningful for ship propulsion or dedicated island/shore microgrids. For context: Commonwealth Fusion Systems (CFS) is building Sparc (~5 m tokamak) as a breakeven demonstration and has raised ~ $3 billion to date; CFS’s Arc aims for grid‑scale generation in the early 2030s. Maritime’s device is larger than Sparc but the company lacks comparable capital and pedigree.

Risks and governance considerations

Technical risks: tokamaks have narrow operational envelopes – plasma control, magnet quench protection, cryogenics for HTS, and handling neutron flux that causes material activation. Maritime’s plan to keep fuel processing on shore mitigates some complexity but doesn’t eliminate radiation and materials challenges from fusion neutrons.

Regulatory & liability risks: There is no established international regulatory framework for fusion on ships. Ports, flag states, and insurers will demand new standards. Even if fusion avoids fission‑style meltdown risk, neutron activation and tritium management present safety and environmental compliance issues.

Financing and schedule risk: projecting a 2032 operational unit from a $4.5M seed base is aggressive. Expect several larger funding rounds, strategic partnerships (shipbuilders, navies, utilities), and multi‑year testing before deployment.

Competitive and market fit

This is a niche market play rather than a challenger to grid incumbent renewables. Early fits include specialized vessels (research, offshore installations, military), island or remote shore microgrids, and repowering high‑value ships where fuel price per MWh is already high. It’s realistic to expect fusion to win economically in high‑value, high‑fuel‑cost contexts before it becomes cost‑competitive on the bulk power grid.

Recommendations – who should do what, and when

- Maritime operators and shipowners: Monitor tech milestones and avoid early procurement commitments. Begin low‑cost pilots with shore‑based fusion or microgrid partners once proof of sustained net energy gain is demonstrated.

- Investors: Treat seed announcement as signal of market framing, not technical readiness. Expect capital risk through multiple dilutive rounds; prioritize teams with deep plasma and systems engineering experience.

- Regulators, insurers, ports: Start cross‑sector working groups now to draft certification requirements, emergency response protocols, and material activation limits — late standards will bottleneck any early deployments.

- Strategic partners (shipbuilders, navies, utilities): Explore partnership or offtake agreements contingent on technical milestones; secure HTS supply lines and plan for retrofitting and decommissioning pathways.

Bottom line: Maritime Fusion’s Yinsen reframes an important question — can fusion find niche early customers outside the grid? The idea is defensible but speculative. The company must convert early engineering proofs (HTS cable assemblies, magnet tests) into sustained plasma energy gain and then navigate a hard sequence of funding, regulation, and marine operations before 2032. Executives should watch milestones, engage regulators, and prepare conditional partnerships rather than commit capital today.

Leave a Reply